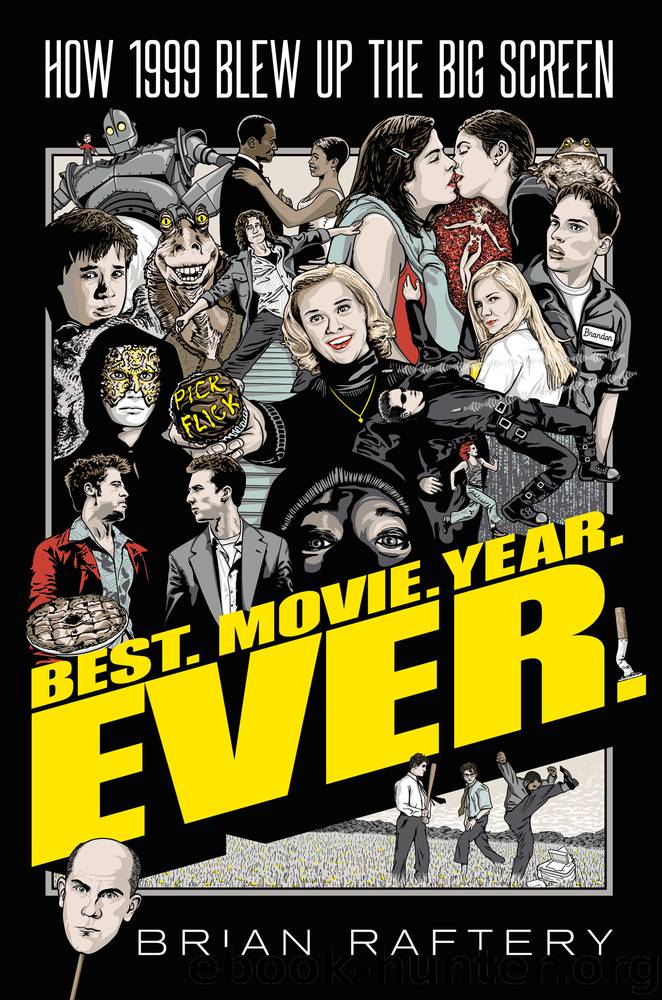

Best. Movie. Year. Ever.: How 1999 Blew Up the Big Screen by Brian Raftery

Author:Brian Raftery [Raftery, Brian]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 1501175386

Google: iMaNDwAAQBAJ

Amazon: B07GNTR717

Goodreads: 40538583

Publisher: Simon Schuster

Published: 2019-04-15T16:00:00+00:00

10

“IT’S KARMA, BABY.”

THE BEST MAN

THE WOOD

When Taye Diggs first started going out for screen roles in the nineties, he would occasionally carry a black, tight-fitting skullcap in his back pocket. So would some of his African American peers. “We had a joke that even if we were at a Shakespeare audition or a classical audition, we’d have our thug hats with us,” says Diggs. “That way, if we got a call to try out for something in movies or television, we could put it on and immediately play a thug: change your dialect, mumble your vowels, cut off consonants.” Diggs, an actor and singer raised in upstate New York, would wind up spending long stretches of the decade onstage in New York City—he was a member of the original cast of Rent—in addition to picking up the occasional TV part. But he was leery of some of the film roles available to twentysomething black actors at the time. Diggs was trying to find movies “where you just see African American people being people, as opposed to stereotypes,” he says. “Nobody is a drug dealer, nobody is a thief.”

Diggs had arrived in New York just a few years after the African American movie renaissance of the late eighties. It was a period in which studio executives suddenly started paying attention to the films and filmmakers they’d long ignored. “In Hollywood, Black Is In,” noted a 1990 New York Times article, referring to a rush of talent led by Do the Right Thing’s Spike Lee and carried on by such writer-directors as Keenen Ivory Wayans (I’m Gonna Git You Sucka), Robert Townsend (Hollywood Shuffle), and Reginald Hudlin (House Party). They were all part of a new league of African American filmmakers whose work had been both critically laudable and commercially viable. And the big studios were now very eager to work with them. “Having a successful black film gives a studio a great social profile,” Wayans said at the time. “It makes the executives smell like roses.” Lee, as usual, put it even more bluntly: “Hollywood doesn’t care what kind of films they are as long as they make money.”

Within a few years, Lee would release Malcolm X—then the highest-earning film of his career—and John Singleton would become the first African American nominee for Best Director for his hit drama Boyz N the Hood. Those epochs were followed by the arrival of such filmmakers as the Hughes brothers, Rusty Cundieff, Kasi Lemmons, F. Gary Gray, and Julie Dash, among several others, as the renaissance turned into a full-on revolution. In 1991 alone, noted the Times, there were nearly twenty African American–aimed films set for release—a record number. “Black film properties may be to the ’90s what the car phone was to the ’80s,” noted the Times. “Every studio executive has to have one.”

Yet those execs tended to have limited imaginations about what kind of black movies could succeed. The nearly $60 million success of Boyz N the Hood was part of a decadelong run of what would become known as hood films: tough, violent, inner-city-set dramas.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Kite Runner by Khaled Hosseini(4500)

Gerald's Game by Stephen King(3941)

The Perils of Being Moderately Famous by Soha Ali Khan(3795)

Dialogue by Robert McKee(3602)

Story: Substance, Structure, Style and the Principles of Screenwriting by Robert McKee(3002)

The 101 Dalmatians by Dodie Smith(2951)

The Pixar Touch by David A. Price(2752)

Confessions of a Video Vixen by Karrine Steffans(2690)

Fantastic Beasts: The Crimes of Grindelwald by J. K. Rowling(2557)

How Music Works by David Byrne(2554)

Slugfest by Reed Tucker(2432)

Harry Potter 4 - Harry Potter and The Goblet of Fire by J.K.Rowling(2426)

The Mental Game of Writing: How to Overcome Obstacles, Stay Creative and Productive, and Free Your Mind for Success by James Scott Bell(2403)

Wildflower by Drew Barrymore(2124)

Scandals of Classic Hollywood: Sex, Deviance, and Drama from the Golden Age of American Cinema by Anne Helen Petersen(2117)

Casting Might-Have-Beens: A Film by Film Directory of Actors Considered for Roles Given to Others by Mell Eila(2078)

Screenplay: The Foundations of Screenwriting by Syd Field(2075)

Robin by Dave Itzkoff(2016)

The Complete H. P. Lovecraft Reader by H.P. Lovecraft(1984)